From inflation risks to risks to financial stability and back

Key points at a glance

- The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, as well as the forced takeover of Credit Suisse by its rival UBS, sparked fears of a repeat of the banking crisis of 15 years ago

- Whereas three years ago it was mainly equity market volatility that was in crisis mode, today it is the anticipated fluctuations on the bond side that are keeping investors on tenterhooks

- The banking crisis will be forgotten relatively quickly and inflation will move centre-stage again

It's almost exactly three years since the peak of the Covid-19 crisis. For financial experts, it's almost a natural reflex to equate the low point of the market in March 2020 with the peak of the crisis. Regardless of the exact dates, it's fair to say that this crisis is over. But we didn’t have long to wait for the next one.

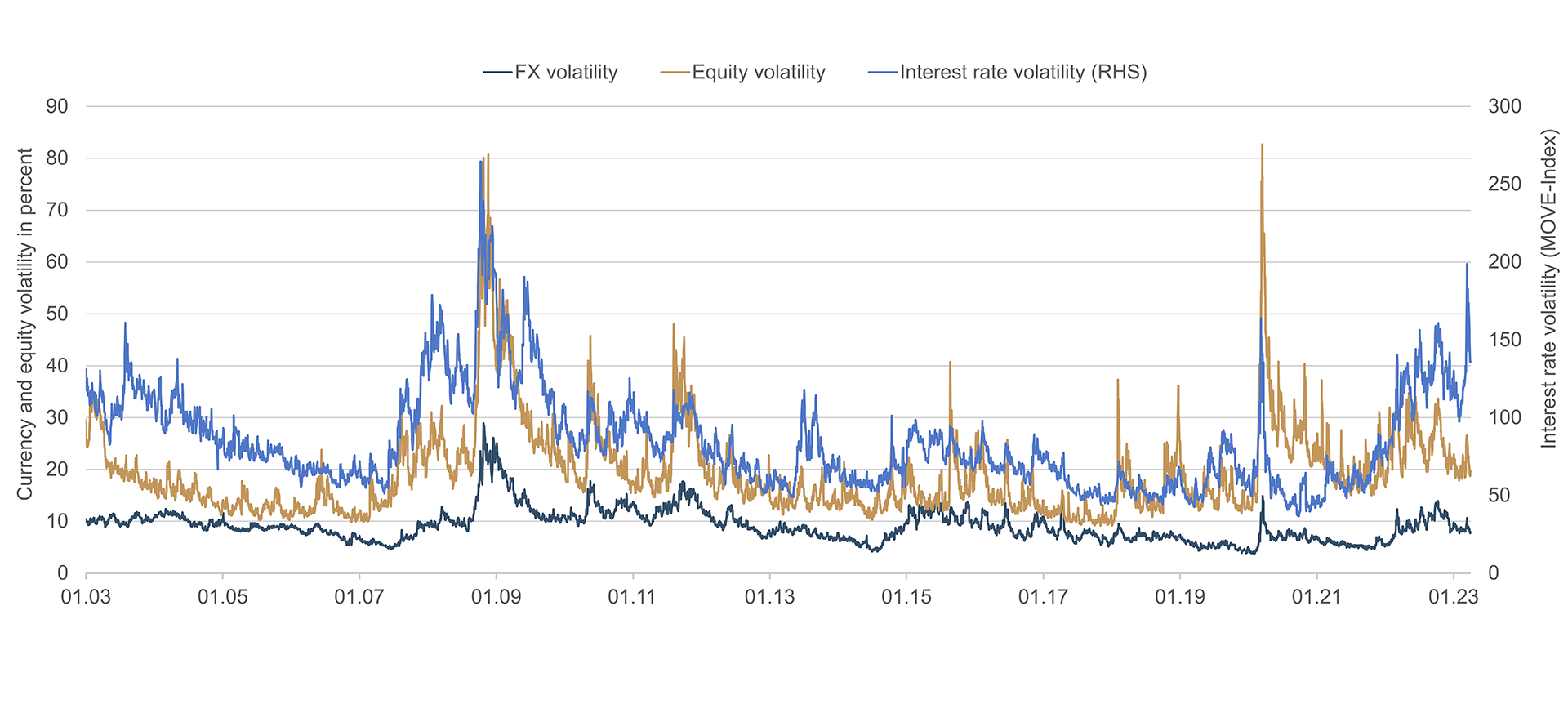

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, as well as the forced takeover of Credit Suisse by its rival UBS, sparked fears of a repeat of the banking crisis of 15 years ago. Even without looking at the pages of the newspapers, it's quite clear from the implied volatilities of traded options on the various asset classes whether a normal correction or crisis is priced in. It is interesting to note that at the moment it is the volatility in interest rates rather than equities that is causing a stir. Figure 1, for example, shows the implied volatilities for equities, bonds and currencies over the last 20 years.

Whereas three years ago it was mainly equity market volatility that was in crisis mode, today it is the anticipated fluctuations on the bond side that are keeping investors on tenterhooks. Historically speaking, such high interest-rate volatility has tended to correspond to a VIX index at around 50-60, i.e. significantly greater equity stress. Here, however, the point is not the ostensible break in this relationship but future developments on the interest-rate front. The future course of efforts to combat inflation as well as the way in which the current banking crisis is handled are obviously important determinants. Although over the past year we have seen the fastest rate hike cycle in recent decades amid efforts to restore monetary stability, developments in recent weeks have led to a sharp fall in rates over a very short period. The high realised volatility consequently resulted in substantial expected (implied) volatility. The question, therefore, is what happens next?

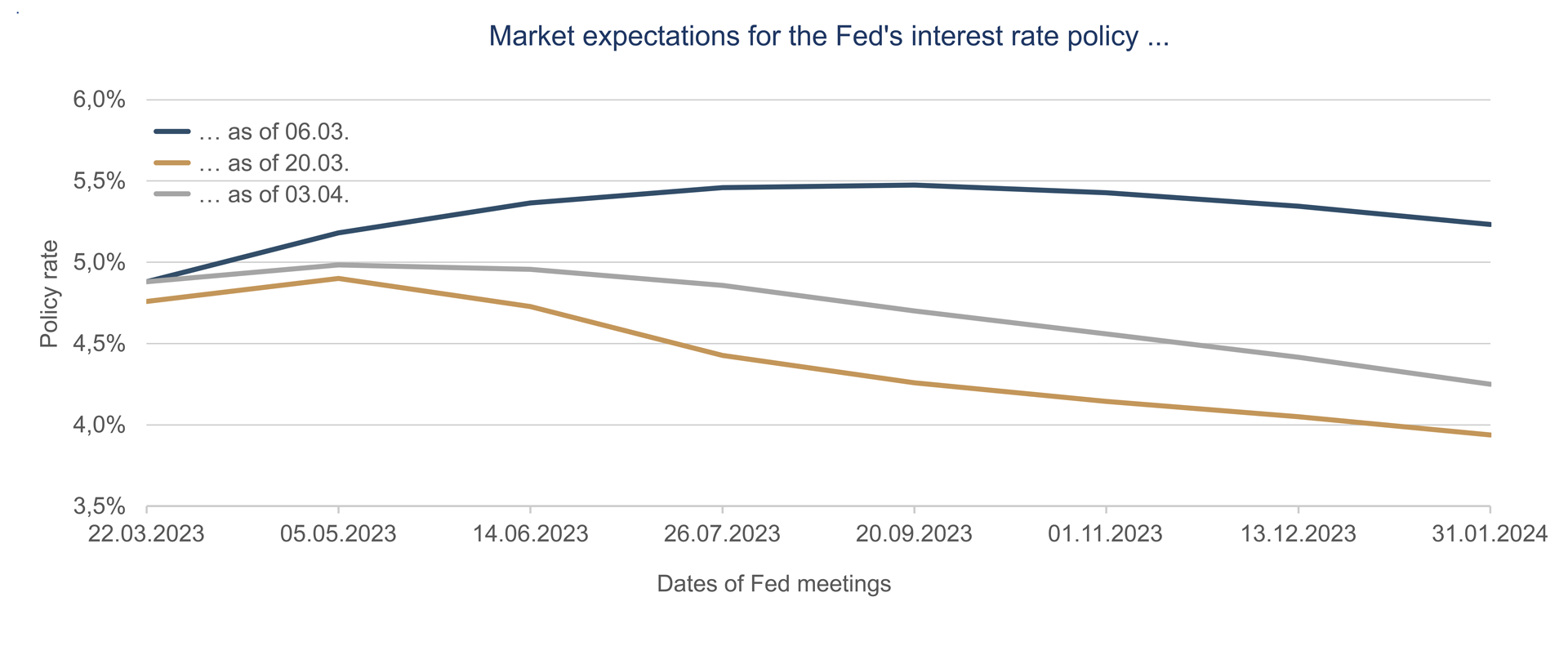

The current narrative goes as follows: recent stress in the banking sector should help central banks combat inflation through a tightening of lending and credit terms for the banking sector – and small banks in particular. In other words, the tightening of financing conditions will cancel out a portion of the rate hikes necessary to bring inflation back down to the Fed’s 2% target. In light of tensions in the banking sector, markets anticipate that fewer rate hikes will be necessary – not because there won't be any inflation, but because stricter lending standards will do the job in full or in part. Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that investors' expectations regarding Fed and ECB monetary policy have changed dramatically. Expectations of further rate increases have been superseded by expectations of several rate cuts in a very short space of time. Figure 2 shows the Fed's expected (i.e. priced in by the market) interest rate policy at three key points in time: 6 March 2023 (before the crisis), 20 March 2023 (Monday of the CS takeover) and currently (3 April 2023). It is clear to see how radically all interest rate hikes were priced out of the market on 20 March. A degree of perspective has returned since then.

"We think the impact of the banking crisis

on the real economy is currently overdone."

Michael Blümke

However, our assessment of the situation regarding interest rates leads us to a different conclusion. The crisis among the banks will be forgotten relatively quickly and inflation will move centre-stage again. We think the impact of the banking crisis on the real economy is currently overdone. First, we shouldn't forget that these are idiosyncratic risks that can be stemmed relatively quickly. Second, we think the measures taken by the Fed and the Treasury Department to provide liquidity, calm and, above all, confidence are sufficient. Decision makers in the U.S. have learned from previous crises and this time the response has been "big and fast". The protection afforded to all investors and the provision of liquidity have reduced the risk of an immediate bank run as well as the likelihood of a broad-based bank run on a lasting basis. To reduce future adverse impacts, the Fed has additionally created a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

In addition to the temporary discount facility, where a broad range of securities can be borrowed against at a discount to market value, the BTFP offers banks liquidity for a one-year period at the par value of U.S. Treasuries, mortgages and agency debt. What's important is that these facilities enable banks to obtain liquidity in an orderly fashion instead of having to look for funding or sell assets at a discount and realise losses, which would in turn increase the probability of a further withdrawal of deposits. To assess the impact on the real economy, it is important to understand the role played by the banks in the U.S. credit system. The crucial factor here is that bank loans account for a relatively small share of borrowing by the private sector.

Indeed small banks provide about 2% of GDP, large banks 3%, while the lion's share of loans come from the capital market and other sources. This indicates that bank lending has only a modest influence on the economy. If we take the weekly bank balance sheet data, we can also see that the financing activity of the banks had already slowed last year – that is, prior to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. The current crisis and migration of deposits from small to big banks could accelerate the slowdown in lending by small banks; however, growth in lending by the big banks that are the beneficiaries could partly offset this. Overall, therefore, it is uncertain whether the stress in the banking sector and its implications for lending activity will cause a reduction in growth that corresponds to one or more rate hikes.

What hasn't changed, however, is the fact that inflation continues to pose a problem. The labour market remains tight, excess household and corporate savings accumulated during the pandemic still exist, and income and spending growth seems to be stabilising at well above the level that would be commensurate with inflation running at around 2%. This pressure still needs to ease significantly. Unless the current financial stress results in an abrupt slowdown in economic activity, it will be difficult for the Fed to move to a less restrictive stance – let alone reduce interest rates. If central banks are successful in stemming the risks to financial stability as planned, inflation risk could – and will – soon come back to haunt them.

Please contact us at any time if you have questions or suggestions.

ETHENEA Independent Investors S.A.

16, rue Gabriel Lippmann · 5365 Munsbach

Phone +352 276 921-0 · Fax +352 276 921-1099

info@ethenea.com · ethenea.com