Inverted yield curve: Harbinger or cause of recession?

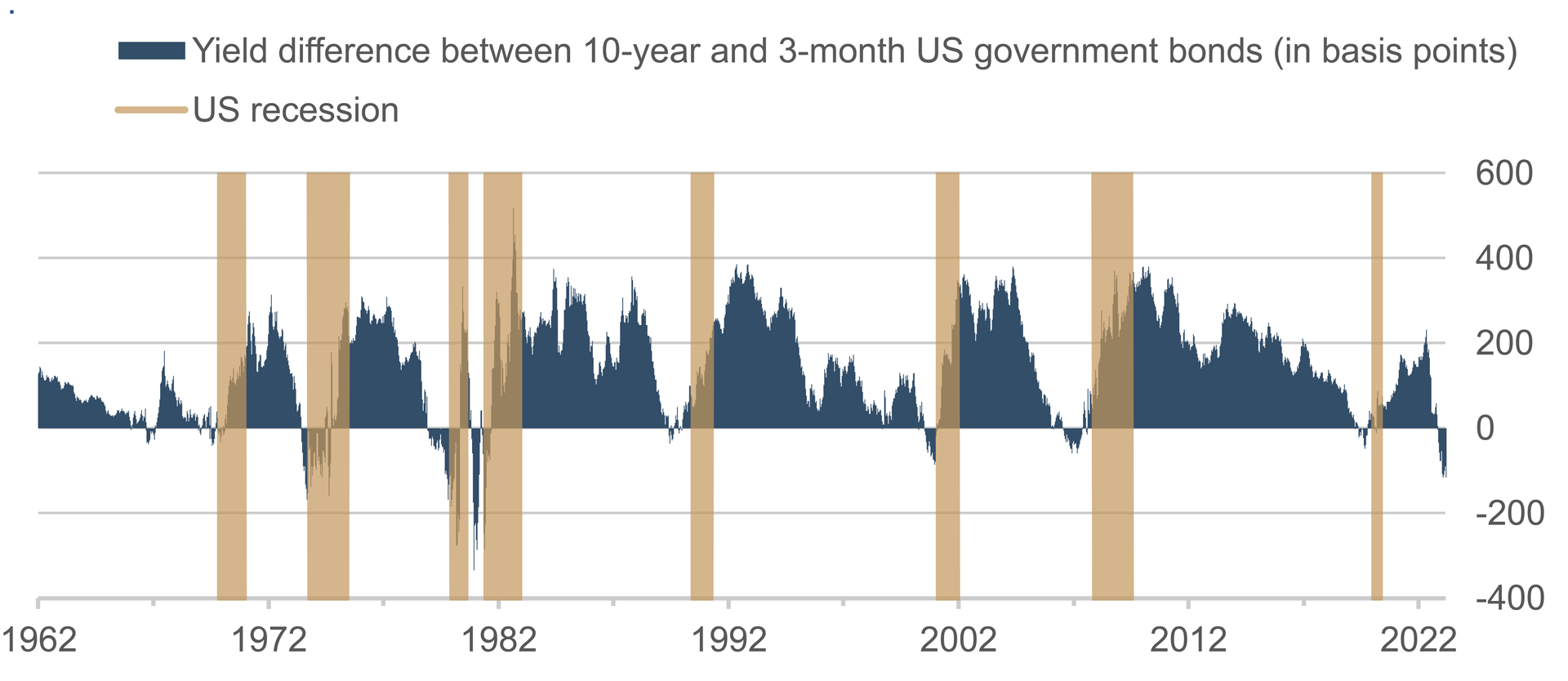

Long-dated U.S. Treasuries are currently offering a lower yield than their short-dated equivalents. The spread between 10-year and 3-month U.S. Treasuries, for example, fell to a temporary low of -133 basis points in March – meaning the yield curve was the most inverted it has been in over 40 years. This is not normal. A normal yield curve slopes upward: the longer the maturity of a bond, the higher the yield. Right now, however, the opposite is the case. This inversion indicates that bond-market participants do not think the current high level of interest rates will last the long term – whether due to expectations of a fall in inflation and/or fading economic growth.

The latter is a good argument as to why the inversion of the yield curve is a closely watched indicator of imminent recession. At any rate, all U.S. recessions since the 1960s have been preceded by an inverted yield curve. So, it is indeed a very reliable indicator.

Nevertheless, there is also a causal aspect as far as the real economy is concerned. Fact is, the upward slope of the yield curve is the basis for lending business. Banks borrow money in the short term (and at low cost) and lend it out over the long term (at higher interest rates) – maturity transformation, in other words. An inverted yield curve makes long-term lending unattractive and slows credit growth as well as investment. These are classic signs of a recession. So, as well as having prophetic qualities, the bond market makes a self-fulfilling contribution to recession.

The recent failure of smaller U.S. commercial banks highlights the fact that the current, inverted yield structure is already inflicting damage on the real economy. Time will tell whether the inversion theory is proved correct this time round and recession follows. History shows that there have been isolated instances of false positives – cases in which there was indeed an inversion, but this was not followed by recession.

Please contact us at any time if you have questions or suggestions.

ETHENEA Independent Investors S.A.

16, rue Gabriel Lippmann · 5365 Munsbach

Phone +352 276 921-0 · Fax +352 276 921-1099

info@ethenea.com · ethenea.com